Contents

Categories

Fifteen years ago, I found myself in the middle of a major digital transformation at the world’s biggest publisher of offline magazines, Time, Inc. As the global publishing arm of Time Warner, Time Inc was hugely profitable and home to some of the world’s most prestigious and successful magazine brands.

To quote Ron Burgundy, we were “kind of a big deal”. However, recognizing the rise of the internet as a platform for content and an important channel for our audiences, we had set course to think beyond the boundaries of our brands and become a digital-first content business.

The company had attempted this journey once already; with a false start and millions of dollars burned during the “dot com bubble” of the late ‘90s. At that time I was working for a small start-up media company that was agile and had already successfully capitalized on digital publishing (one of the few to have actually made a profit back then).

However, Time Inc, like many other big players, invested heavily but failed to find profitable models. Perhaps a little early to market in some respects but exacerbated by the wrong strategy and underestimating the scale of the business-change required. Budget was ultimately pulled, the new “digital” division was closed, and it would be almost a decade later that a new concerted effort to digitize would once again headline the corporate strategy.

This time, with a better plan, but by now late to the party thanks to previously burned fingers, short-term investment priorities, and an institutional belief we were too big not to succeed. At the time of this digital resurgence, I was a commercial leader with a seat on one of the Divisional Boards, and a member of the Advertising Board, which was collectively responsible for establishing new monetization models and reinventing brands and advertising products for the ‘digital age’.

If you’re interested, I write more about this experience in my new white paper, available here. I also spoke about this topic in more detail in a recent ESOMAR webinar, “Transforming data collection without paralysing your insights business”, which you can now view on demand.

The digital transformation of the ad industry (although we never called it that at the time) had started long before Time, Inc’s ill-fated undertaking in the late 1990s. From the early 1990s many of us first began selling static banner ads and tenancy sponsorships on primitive websites, trying at first simply to replicate the way this had been done for years with our offline products.

Telephone calls and sales lunches with clients and ad agency buyers, negotiating packages based on how many “hits” our home pages were getting. I remember cover-mounting CD-ROMs to our magazines with the first versions of Explorer and Firefox browsers in a bid to get more readers to “go online”.

But as web traffic grew, browsing speeds exploded, and advertisers became savvier to the volume of ad impressions needed to deliver successful campaigns, it became clear that traditional human-based sales models would not scale, for either buyers or sellers of ad inventory.

Enter; the ad networks, ad exchanges, demand-side platforms, supply-side platforms, data platforms, and nearly 3,000 tech players all vying for a slice of an emerging and more efficient digital ad market. By the mid-2000s, advertising was becoming increasingly automated and programmatic.

Products were becoming more sophisticated in order to meet consumer and advertiser demands, and advertisers wanted to buy larger audiences and tap into audience data to make smarter, real-time campaign-buying decisions. At Time, Inc. we were seeing our ‘offline dollars’ converting and diminishing into ‘online cents’ as the media world fragmented and new players emerged.

This meant we had to find ways to simultaneously scale up our offerings and step-change our efficiency. However, by the time I arrived on the Advertising Board, it was becoming obvious that none of our legacy technology matched or supported our digital ambitions.

So, we began multiple programmes to implement a host of new platforms which would help us build better products; capture and utilize consumer data; monetize our audiences more programmatically; and – critically – transform our internal processes and our efficiency in sales, operations and delivery.

Throughout the next decade and a half, we implemented sales and marketing automation platforms. We were Salesforce’s first significant media customer in Europe, for instance, and an early customer of Zuora, the leaders in subscription management as we sought ways to package and bundle products differently for consumers.

As well as automation technologies, we embedded data and analytics tools, plethora of advertising optimization tools, and content management platforms.

You name it; we tried it. But, despite all the new tech, we encountered significant roadblocks when it came to achieving our goals. Teams were struggling to keep up with the changes required to sell and deliver the huge array of new digital products and packages we were now offering. There were two reasons for this.

First, we needed to invest more heavily in retraining our people. It is well known that any transformation or change programme has to consider the implications for people, processes and systems. We used to say: “You can programme the computers, but you can’t just programme the people.” The second reason was simply that our own internal sales and operations systems were themselves a blocker to this people and process transformation.

Our order management tools, our CRM, our financial systems (ERP), and our ad ops systems were all designed for selling simpler, more linear offline products. The systems did not talk to each other and were not fit for purpose, meaning that too often our go-to-market plans could not be efficiently executed by the teams on the ground.

We couldn’t process or deliver the packages we were selling, invoice for them, or track and report on performance, for example. Even our P&L structure was antiquated, and we were constantly forcing round pegs into square holes; digital products delivered with analogue systems and reported under ill-fitting headings on excel spreadsheets.

The quickest fix of course, a team in India crunching massive excel files into huge daily reports. So, we initiated a programme to upgrade these business-critical tools, and to integrate them more efficiently in order to make step changes to our workflows. Seeing that our tech teams were craving a bridge between them and the objectives of the board, and having at least some technical understanding, I volunteered to fulfil the role of “commercial owner” of the program.

Here’s where the fun and hard learning started. From the outset, as we analyzed our business and functional requirements, and compared them to the systems we had, it was obvious the gaps were huge. Virtually all of our tech was on-premise at a time that Cloud Software as a Service (SaaS) was beginning to take off.

Some was our own proprietary code, some was licensed, but all of it lacked the configurability that Cloud SaaS could offer. To make the changes we needed would mean writing a ton of custom code, employing a small army of developers and consultants, and again smashing square pegs into round holes by adapting platforms far beyond the purposes of their original design.

From the get-go our recommendation to the board was to start over with new SaaS vendors and configure these new agile tools to our purposes, whilst rationalizing the number of systems and integrations needed. However, whilst our CFO agreed this would be the ideal route, it was insisted that this approach would “likely take too long and be too expensive, so we must use what we already have and make it work!”.

Millions of pounds and seven years later – with one project team member giving birth to two children and returning from a second maternity leave to find the programme still going – we finally pulled the plug. Yes this actually happened. We did achieve some small results with incremental benefits. But, sadly, the programme was doomed from the start.

By choosing to build, or adapt, our existing systems and integrations, we were responsible for the design, usability, and cost of development. But more than that, despite adopting agile development methodologies, we were hard-coding solutions as we went along. Along with every additional integration between platforms, we created multiple dependencies that would begin to cripple the next iterations of development.

Indeed, the implications of small changes led to exponential upstream or downstream complexities. With every step, we unwittingly added a layer of technical debt and more barriers to the next iterations and enhancements. To put things in context, this happened to be a period that saw the biggest structural changes in the history of the media industry.

While we were building systems for the business we had now become, based on change that had already happened, the dynamics of that business were changing again at an alarming and accelerating pace, in ways we could never have imagined. Soon after we started the project, Steve Jobs’ Apple Inc. invented the iPhone, then the iPad.

A plethora of new apps created new advertising products, while 3G put broadband internet speeds into the palms of our hands. New online ad formats were being imagined every week. Programmatic ad networks and technologies exploded, with new revenue models and sales channels.

Those 3,000 new ad tech platforms emerged, leading to a need for the now infamous adtech market “Lumascape” infographic to help make sense of it all. And, thanks to the accounting scandal of Enron – and to some degree our own parent company, Time Warner – new accountancy practices came into effect with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, meaning we had to flip the entire way we recognized and invoiced digital media revenues.

Finally, the time came to redesign the entire P&L structure, which itself had implications for our systems. It wasn’t just a moving target. Our universe was spinning and showed no sign of stopping. The rug was repeatedly pulled from under our feet just as we thought we’d cracked the next piece of the puzzle. Under those conditions, you might think we had set ourselves an impossible task. However, with the benefit of hindsight, it was not the task that was the problem, but how we went about trying to solve it.

We had “platform-architected” ourselves into a corner, and built a rigid system that was near-impossible to adapt to change; laden with complex lines of code. Eventually, somewhat scarred, we changed course. We scrapped key pieces of software, partnered with agile, configurable SaaS vendors with open-APIs to enable simple, adaptable integrations between platforms. Anything we kept was utilised only for what it was good at and intended for.

We minimised the number of integrations between systems by leaning on platforms such as Salesforce, which could be extended with its out-of-the-box marketplace of software vendors with tools built natively on its foundational infrastructure “Force.com”. Ultimately with this approach, success then came quickly, at far lower cost, and we had a set of tools that were adaptable to whatever innovations may come next.

What was previously a threat – new digital innovations we couldn’t harness – became an opportunity, thanks to our ability to adapt quickly and be first to market with new innovations. Salesforce itself has arguably become the fastest and biggest success story of any enterprise software company.

This can be attributed, in part, to its ease of configurability and its thousands of native or integrated partners that enable companies to deploy full enterprise software solutions, way beyond CRM, with relatively minimal integration or customisation effort. They may just be onto something! On reflection, our lessons learned should not have been so surprising.

Charles Darwin is famous for observing that it is the most adaptable of the species, not necessarily the strongest, that survives. MIT Business School have, apparently, taught for a number of years that businesses should organise to facilitate ‘Continuous Innovation’ because the future has become so unpredictable.

Since this period at Time Inc. and latterly my experience working in Enterprise Technology alongside Salesforce and its consulting partners on numerous similar large transformation programmes in many industries with comparable challenges such as Telecommunications, I have firmly adopted this as my own mantra: Architect your business to evolve unhindered by your technology.

What does this have to do with the insight industry?

The insight and market research industry shares many parallels when it comes to the structural changes that media (and telecommunications for that matter) has been through. Undoubtedly, the world of market research right now is in the midst of an extended and unprecedented period of major change.

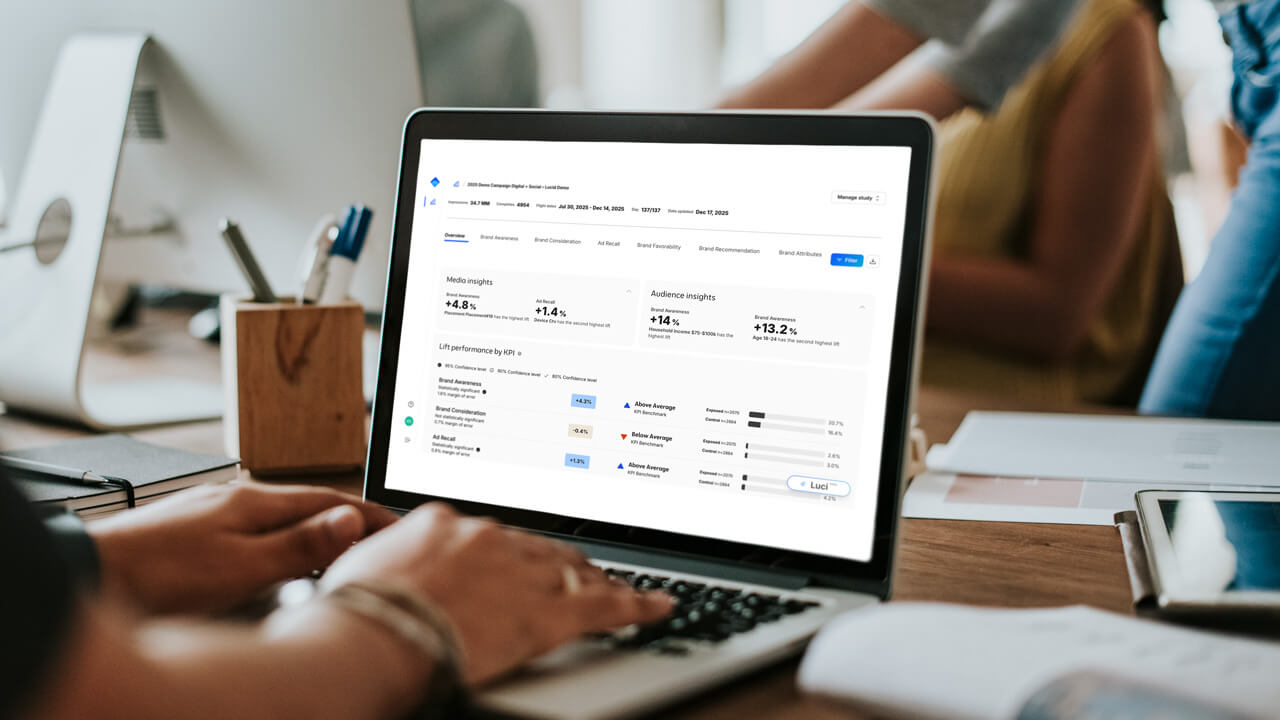

In so many ways this is, arguably, the most exciting period in the history of the business, with multiple opportunities to use data in more sophisticated ways to derive insights that can be converted more directly to action and outcomes which are more easily measured. But it can be daunting working out how to adapt and what technology to adopt. And, like in media, the pace of change is not going to slow any time soon.

New ways to engage consumers will emerge, new technologies, new data, changing regulations, evolving demands from marketers and new insight products. At a very high level, we can learn from my own experiences in the media industry and other large-scale digital transformation programmes in a variety of spaces.

It’s clear that we must utilise solutions that are future-proofed, adaptable and, where possible, limit upstream and downstream dependencies. It’s also clear that trying to develop many of these solutions in-house can create a massive amount of technical debt, strain on internal resources and a loss of focus on critical company goals.

Innovation dies, and companies who attempt this feat are quickly left behind. It is important to consider not what you “could” build, but what you “should” build yourself or when to partner to accelerate your time to value and safeguard adaptability. I encourage you learn more by viewing my recent ESOMAR webinar.

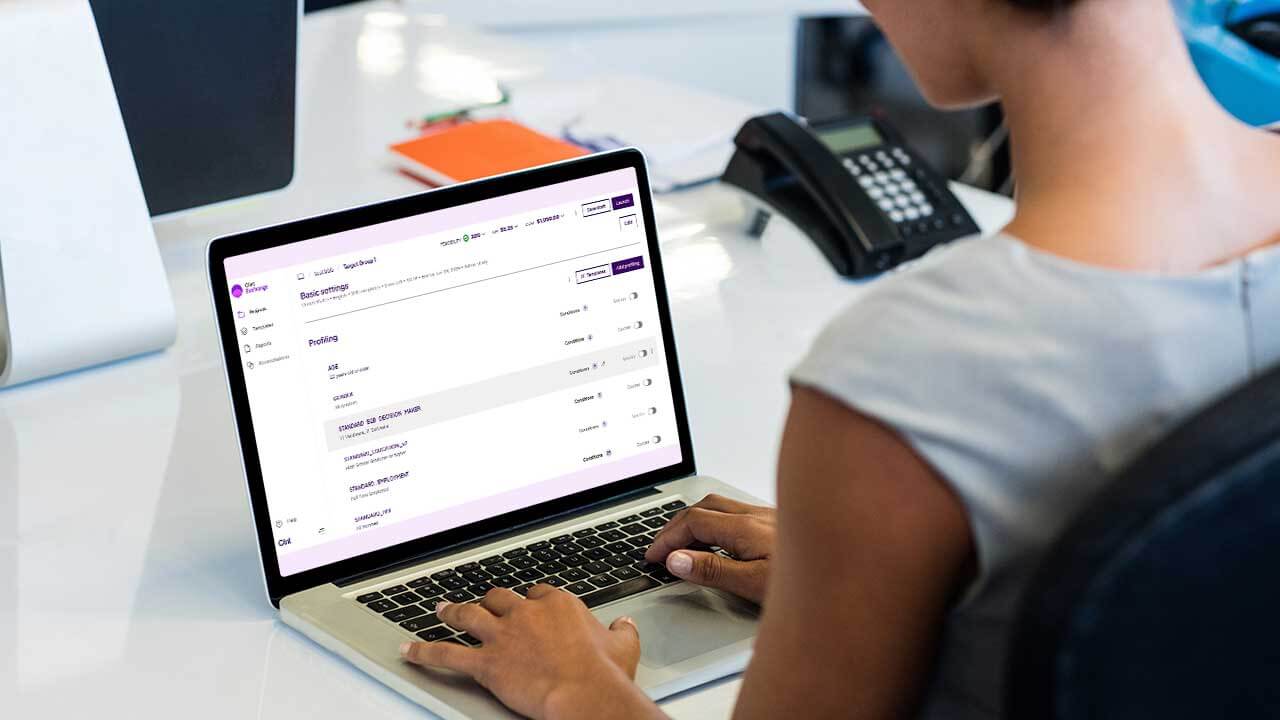

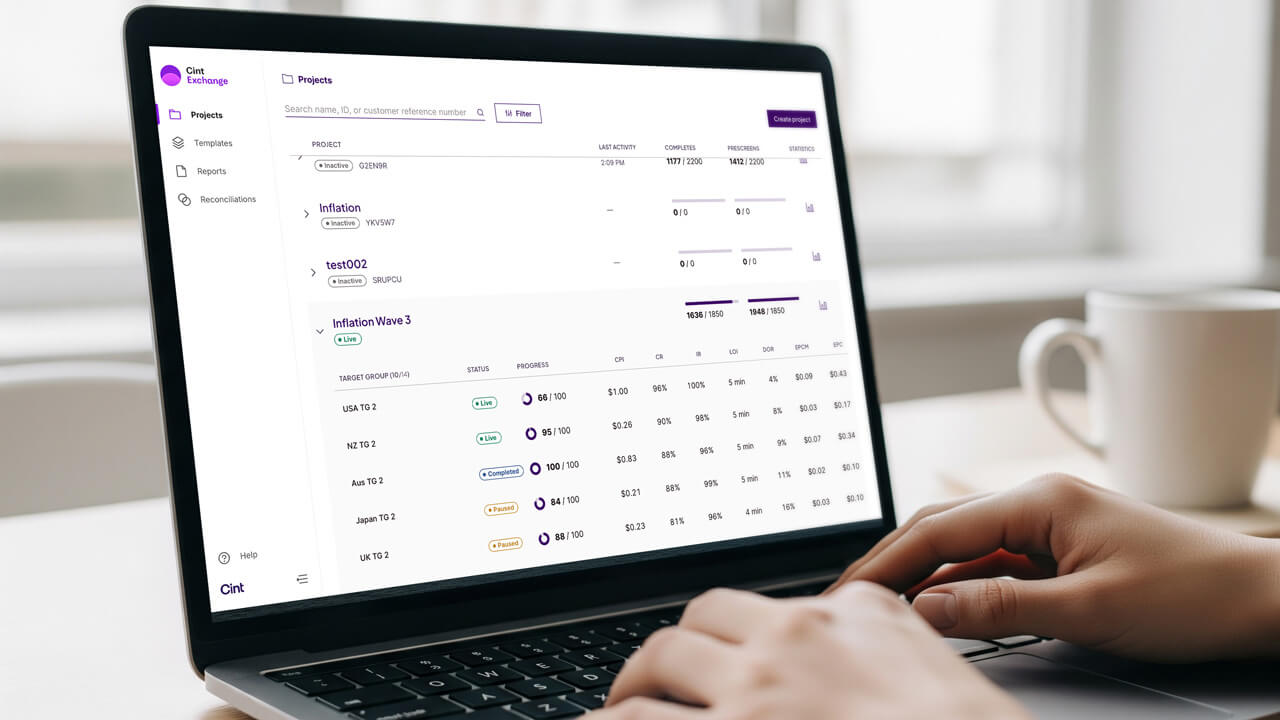

During the session, I laid out critical considerations for successful insights automation, all within the context of the current insights landscape.

There is no doubt: the decisions insights companies make today regarding automation will spell the difference between staying in business or falling by the wayside.

We must look beyond the industry’s persistent mantra of “faster, better, cheaper” and tap into genuinely scalable and future-proof processes using adaptable software solutions that are designed to address the unique challenges faced by market researchers, and, in this way, be ready for the next phase of change.

A smart approach to automation is essential to power more efficient access to insights at scale. Organisations that partner with those who can help them deliver their vision, keeping their focus on business priorities, will have the best success.

The right partnerships will provide the space to innovate and adapt quickly in the face of further disruption. This is, more than ever, the single best path to long-term prosperity. View the webinar on demand.