Three Hypotheses. Three Challenges.

The impact of the new coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is expected to be massive and global. While market researchers have experienced previous crises, they are all unique in impact and thus impossible to predict. Nevertheless, our operating hypotheses are always the same, even if the outcomes differ:- People’s purchasing or consumption behaviour changes

- People’s demographics change

- People’s participation levels in research change

- We have no idea how long the crisis will last.

- We have no idea what the magnitude of the effects will be.

- People are often anxious about these issues and thus tempted or pressured to make preemptive or presumptive changes to the data.

(1) Changes to consumer purchasing and consumption

Problem Changes in behaviour are always predicated on the nature of the crisis and the categories/sectors affected. In the current crisis, certain things are easy to predict. Anything related to travel is crashing in front of our eyes. We will surely see an increase in the use of food/grocery delivery services. Moreover, we are likely to see changes—and potentially dramatic ones at that—in consumer brand loyalty. How many people knew of Zoom prior to this crisis? In the words of former U.S. Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, these are the “known unknowns.” Why it is important Opinion on this topic spans the range of possible solutions. Some feel that because the change is episodic it therefore must be suppressed or smoothed out of the data since, at some point, things will go back to normal. Others (myself included) believe that, since the change is indeed real, it needs to be accounted for. You need to decide for yourself where you fall on the issue. Recommendations The best we can do in these situations is to continue to track desired behaviours over time and look for changes. To do this: 1. Track raw incidence at the category level If you have not been doing this already, look for data available from reliable providers who observe trends in the given category. 2. Track brand use and look for changes Look closely at brand use questions. You may even want to revisit lists of brands you always ask by fielding unaided brand awareness questions. Alternatively, qualitative research, social media discovery, and even scanning newspapers and online news sites can help identify shifting loyalties. 3. Re-evaluate tracker sample designs There are two basic ways to design a tracker sample. One is to ensure that the people who arrive at the qualifying question for the study are representative of the total population you are trying to reflect. The other is that they are not. Put differently, for your data to provide unbiased estimates of a known population, they must be representative at the point at which you decide someone is qualified or terminated. For at that point, you can weight/project the data to arrive at market estimates. Acceptable variations to this include adding augments/boosts to the sample which give you greater resolution on the data (more observations) while representing a known proportion of the population being sampled so their numbers can be reweighted to bring the total estimate in line. The alternative is that you are picking a responding sample structure that is simple reflective of “something” which may or may not be representative. 4. Conduct CHAID/CART analysis linking variables of interest to demographics This is a “pro tip.” Most companies apply cosmetic control for demographics in a sample design (using quotas or post-field weighting) under the principle, for example, that nesting age and gender will mitigate these effects. This is useful, but basic demographics might only explain half the variance of a variable of interest. In this case, decision-tree analyses are useful for identifying other variables or demographic interactions that may impact variables of interest. Knowing this is helpful for the other hypotheses listed below. Whatever your point of view on these issues, if you see strange findings I strongly counsel against any nonfactual manipulation of the data for two reasons. One is that you will only be guessing. The other is that when you artificially change something that is produced in a system, you will be obliged to keep manipulating that datapoint until you stop running the study. We simply cannot predict what is going to happen and therefore it is useless to try to anticipate changes or make premature corrections to sample designs.What Cint is doing Cint itself can provide little insight on overall consumer behaviour. As an exchange that brings buyers and suppliers together, we have no meaningful visibility on incidence in the sectors/categories being studied. To properly look at this, one needs to have been tracking these sectors by country already prior to the crisis and to continue doing so during and after. Nevertheless, we are talking with some of our data collection colleagues to see if we can bring clarity to this situation.

(2) People’s demographics will change.

Problem We use the word “crisis” for a reason. In any crisis, there is typically a great upheaval that affects a significant part of the population. During these times, someone’s residence could change (Hurricane Katrina, Fukushima floods) or net worth could change (dot-com bubble, 2008 U.S. Housing Crisis), or more. An individual’s demographics are pivotal to researchers and sample companies as (a) sample suppliers count on them to be accurate for the sake of targeting and (b) researchers use them to balance/weight the data to reduce bias in the responding sample. Why it is important The real problem here is twofold. One it is that it is not always clear whether respondents are conscious of such changes when they respond to a survey during a crisis. Even if they are conscious, they may not be able to provide accurate assessments of impact (e.g., for net worth) when events are fast-moving. The other is that, if the demographics are changing, it is not just the sample demographics that are changing. The population’s demographics are changing as well. As any survey fundamentally aims to use a sample to represent a known population, the fact that the known population’s characteristics are changing is no small matter. Solution For researchers, basic practice requires that any sample be representative of a known population. There are ultimately two aspects to arriving at final estimates in a study. One is the balancing or weighting of the data should there be any skews in the responding sample. The other is the projection of the data should it be the goal of the study to project overall volumes or values to a total population.- Weighting example: If a population is distributed evenly by gender, then a responding sample of 60% men and 40% women must be adjusted such that the males are given a weighting factor of 50/60=0.833 and the women are given a weighting factor of 50/40 = 1.2.

- Projection example: If there are 1,000 people in the responding sample and 1,000,000 people in the population, volumetrics must be multiplied by a factor of 1,000.

What Cint can do We are exploring increasing the frequency of demographic updates and will be working closely with our supply partners and hosted panel partners on this issue. That said, researchers still have a decision to make as to how they handle potential changes.

(3) People’s participation levels will change.

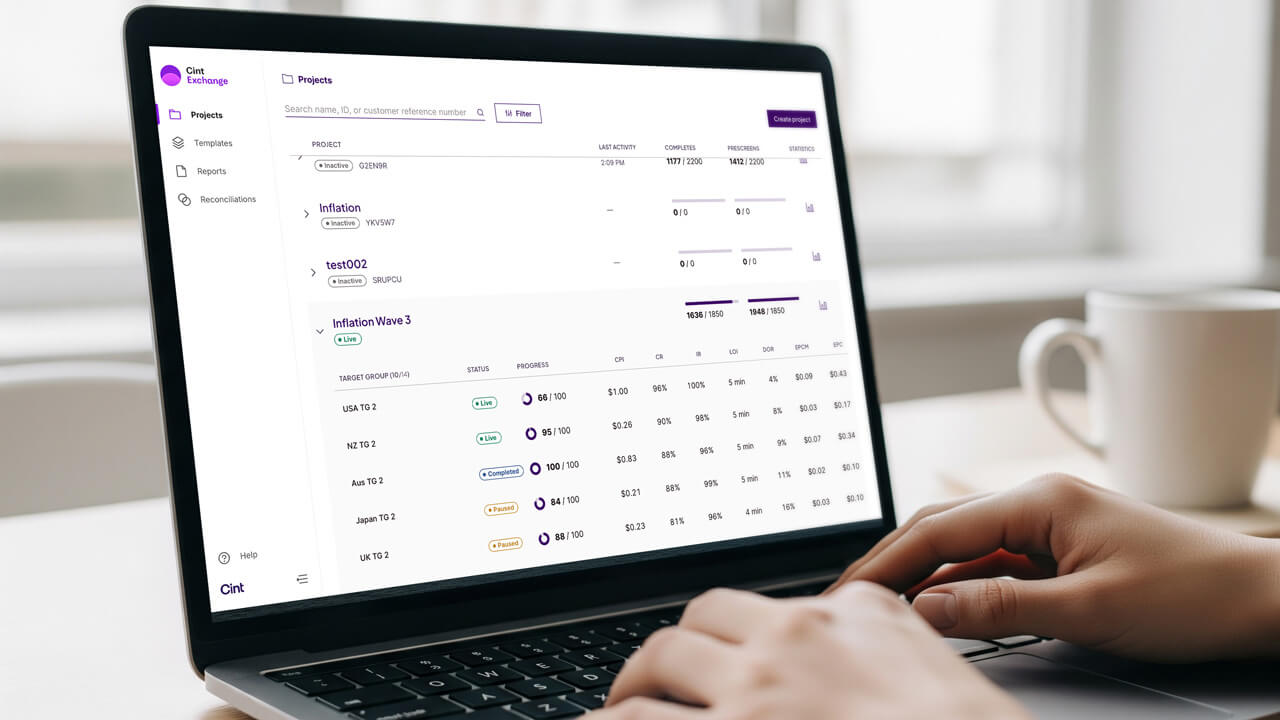

Problem In every crisis, the initial perception is that people will turn away from things like survey participation to focus on their lives. That may be true. And yet, having been through other crises previously I have seen that people keep taking surveys. Who knows why? Maybe they are bored? Maybe they need to escape the gravity of their situations? Maybe they need money? Whatever the reason, this is clearly an empirical question. We cannot guess. We need to look at data. Just as history tells us that real dislocations of the population lead to changes in demographics, it also tells us that people do indeed keep taking surveys. The challenge, as with everything else, is that it is impossible to predict impact and duration. What it means I assume that researchers are managing demographic sample bias correctly (through quotas, sample balancing, or post-field weighting), such that any change in participation that is purely demographic should have no impact on estimates. There will be two main issues that arise. One is that if participation drops, then feasibility for the study is compromised. A small drop in feasibility will be nothing to worry about, even if you fall a few completes short. (Public Service Announcement: Blasting sample into a study for “top offs” is a massively wasteful process that adds no meaningful resolution to the data and has a huge cost in terms of respondent attrition.) For larger shortfalls, a methodologist should be enlisted for help. The second issue would be that these new respondents are systematically different in terms of their behaviour. Researchers have long known that brand new respondents to any study tend to be more “enthusiastic” reporters. Note that this issue should not be confused with the industry bogeymen known as “professional respondents” about which the industry has been wringing its hands for at least a decade. It is indisputably true that because panel companies have historically fished the same waters, there has been overlap across panels. Nevertheless, one of the benefits of automation and programmatic integrations for sampling has been the expansion and diversification of sources. Thus any issues related to participation are likely to be the expansion/reduction of sources from which a supplier may draw, or the uneven flow of new respondents to a study. Solution Controlling for new respondents in a study is more challenging. The easiest way to see if this is an issue is to track the composition of the raw sample by the number of times an individual respondent has participated. Managing this is too complicated to explain in this article. For more information, please contact us. As for the possibility of different behaviour entirely, this may be indiscernible from the episodic behaviour change discussed above. Please reference that section for more ideas.What Cint can do We are monitoring participation related data by day by country. More specifically, we are looking at:These data will provide a complete view of our supply chain and give us a strong indication of the effect of the novel coronavirus on participation. We will be sharing this data in a separate Research Note with clients.

- Entries, completes, and conversion rates from programmatic sources

- Response rates and completion rates from invite-based sources

- Projects and average completes per project

- Confirmed COVID-19 cases per country

Other Questions and Answers

Q. What is Cint’s current point of view on how the crisis will affect the industry and its own business? A. There are plenty of leading indicators suggesting that brands are being hard hit. Whether it is due to consumers staying home, employees staying home, or cash preservation, we expect this will translate into an ebb in demand for research in Q2. We are monitoring several indicators, including cancelled projects, sales pipeline, projects in field, completes per project, and (of course) revenue. Moreover, the uncertainty is causing everyone to be risk-averse and preserve cash. We are also monitoring payment practices on our platform to ensure a healthy ecosystem. Q. What knowledge from markets ‘ahead of the curve’ can we apply to other markets where coronavirus is not yet in full bloom? A. Our hypotheses above will be broadly applicable to all countries. That said, the results will be different based on each country’s decisions as to how they manage the outbreak and any demographic or market nuances in each country. Q. What new in-survey (Quality Assurance) controls do you suggest at this time? A. Fraud never sleeps. We have been fierce advocates for the use of adaptive data-driven techniques that allow us to detect the ever-changing patterns of fraud in survey responses. To find out more about this, please contact your account manager. Q. With everything regarding the novel coronavirus currently, we were wondering if you have any suggested language about the virus to incorporate into surveys, such as “We know it is a difficult time, but think back to your normal routine before coronavirus…” A. If you are going to add language like this, do not make assumptions or apologies about any difficulties the respondent might be facing. Address the facts. If you are going to ask someone about her/his life, give that person a frame of reference. For example: Thinking back to before the outbreak of the new coronavirus, how frequently did you eat dinner out of the home?Written by: JD Deitch (COO at Cint)