Sampling 101

For anyone new to the sample game, this industry may seem like a bit of an enigma. But the purpose of sampling is actually pretty simple: we want to learn the opinions and behaviors of specific populations.

How do we get this information? Surveys. Really strategically targeted ones. We send online surveys to a segment (a.k.a. sample) of people and ask them specific questions. In doing so, we help to paint a picture of demographics across the globe and develop insights about the best ways to reach them.

However, getting surveys to the right people in a way that’s fast, accurate, and affordable has been a complex process. As the need for sample grows, our technology continuously evolves to meet this demand. This is the journey of sampling in the digital age.

In the Beginning: There was Panel, and it was Good (2000 – 2005)

At the dawn of the new millennium, online surveying began to take hold – and eventually, online panels were created. Of course, these panels needed digital respondents to fill out their questionnaires. Very quickly, several email-driven panel companies were built to match this increase in global demand. The concept was simple: recruit online users to join your panel, register and profile them, they take lots of surveys, and everyone wins. Most importantly, almost all the sampling technology was built to recruit and maintain panels. The process of sampling meant pulling user profiles from your database and sending out emails with a link to the market research survey. Simply, a one-to-one relationship between the panel and the survey.

To Panel and Beyond: The Rise of the Router (2005 – 2007)

Online panels worked well, but, as the sample industry expanded, we started to notice a few challenges. In short, we realized that we had a supply problem. As the volume of online surveys started to grow, the demands on panels started to dramatically increase.

One might think that simply recruiting more panelists would be the solution. However, panels suffer from a diminishing returns problem: the first panelist is more valuable than the ones that come after it. Plus, there was no guarantee that all users would respond, qualify, and complete a specific client survey.

So, suppliers began focusing on yield optimization, and eventually the router was born. Routers offered a solution to the respondent qualification problem. With routers, if a respondent didn’t qualify for the first survey, they would be screened against another survey – this solution optimized respondents’ time and qualified them against multiple surveys at once. As a result, routers improved sample capacity and efficiency. They also created a better experience for respondents by offering them more opportunities to complete a survey during their session.

However, as routers became more widely used, researchers began to question their quality and efficiency.

Router concerns

- Bias: If Survey A was prioritized over Survey B, and the surveys were correlated, certain groups of respondents that could have qualified for Survey B were excluded. This could lead to sampling bias if you had few surveys and small numbers of respondents.

- Poor Respondent Experience: To minimize the potential risk of bias, many routers used random assignment in their design – or a combination of both random and priority logic. The process was not as efficient as it could have been, and respondents spent more time screening than necessary, which led to a less-than-ideal respondent experience.

- Control: One often-hidden challenge of a router was that it placed all the control and survey decisioning with the manager of the router. Oftentimes, the router manager wasn’t affiliated with the panel – so matching a respondent with a survey wasn’t always done with suppliers’ best interest in mind.

Note: Research has since shown that even though routers could introduce bias, there is no evidence to suggest that the bias materially affects survey outcomes (Source). The risk is further reduced in routers with large and diverse survey inventories (Source).

Supply Meets Demand: The Conflict of Sample Aggregation (2007–2013)

Even with the increased efficiency and capacity offered by routers, sample companies and research agencies couldn’t get enough delivery out of panels. So, new technologies and techniques were created to source respondents without incurring the cost of recruitment.

The Only Thing Better than Sample is More Sample

To cope with increasing demand and lack of internal supply, sample companies and large sample buyers started down the path of massive sample aggregation. Previously, buyers would only use one panel company per project. However, they eventually realized that using several panels was more reliable from both a delivery and pricing standpoint. And buyers weren’t the only ones blending sample; the sample companies themselves started buying sample from each other at a large scale to supplement the gaps in their own panels. Additionally, this created a challenge for the buyer, as this brokering was mostly hidden from researcher view.

Need Respondents? Look for Loyalty.

Sample companies needed a reliable way to recruit and maintain consistent survey respondents. They saw the positive impact that recruiting from brand-name loyalty programs had on other industries, and they decided to capitalize on that. To increase their supply, sample companies began sourcing respondents from a broad base of companies that offered some version of points, miles, or minutes to a user base. For most of the loyalty-based companies, surveys were initially a small part of their overall revenue but eventually could become the majority. Sample companies became heavily reliant on this long tail of loyalty programs.

Need more Respondents? Take it to the River.

In an effort to further increase supply, sample companies turned to “river” sample. River sample respondents, unlike traditional panel respondents, “are invited online via the placement of ads, offers or invitations. River sample may also be referred to as web intercept, real-time sampling, and dynamically sourced sampling.” (

Source).

They aren’t profiled by the same process as traditional panel respondents. River sampling includes any online individuals who, upon visiting a website or app and clicking on an ad, are directed to take a survey. Rather than relying on a double opt-in process where respondents confirm their interest and are profiled and invited ahead of time, this “in the moment” method takes place dynamically. We may not know anything about these respondents, and after they’ve completed a survey, we may never see them again.

While river sample opened up a new source of respondents to researchers, it has been criticized for the following reasons:

Concerns about River Sample

- Representation: Without a controlled recruitment and invitation process, river sampling can lack obvious census representation.

- Quality: Respondents in river sample tend to be less engaged and are more prone to straightlining behavior.

- Profiling: The lack of profiling information makes respondents difficult to track to engage in future surveys.

With proprietary online panels growing at a much slower rate, many sample companies became heavily reliant on these new sources of sample. Within a few years, the combination of sample aggregation, loyalty programs, and river sources made up the majority of sample that was offered by sample companies.

The Dawn of a New Era: Programmatic Sampling (2013 – 2015)

API: The Great Innovation of Sampling

When we began our API development in 2013, we couldn’t have predicted the tremendous impact that it would have on our business and the industry as a whole.

APIs have completely transformed the way online sample is bought and sold. An API, which stands for Application Programming Interface, is a system communication tool. It uses a common language that both buyer and supplier applications can understand, allowing our software application to communicate with both sample supplier and buyer applications. We connect with a range of applications, such as panel databases, survey platforms, or reporting portals – allowing them to access the features of our platform from their own system.

These connections allowed buyers and suppliers to communicate with each other and deliver sample with unprecedented speed and scale. And, just like that, programmatic sampling was born.

The Supplier Gold Rush

Initially, it was the suppliers that moved into fully API-delivered sample. Why? First, sample is a supplier’s revenue source, so it was easier to justify the technology expense. Secondly, many suppliers already had proprietary panel and yield management technologies that just needed an automatic connection to the surveys.

Enter the sampling platform which aggregated survey inventory and provided access directly via API to the suppliers.

APIs are the hardest to get right, but they also provide the largest long-term value to the supplier. Yes, there are additional product and engineering resources that are required to integrate an API into a sample buyer or seller’s system. But, API is truly the future of modern sampling, and I’ll tell you why.

With an API-driven approach, sample can be delivered more intelligently than routers have allowed in the past. Not only do suppliers control respondent allocation directly, but they can also develop a deeper understanding of their respondents, which enables them to target the right surveys – and the right surveys enable them to accurately match qualified respondents with survey opportunities in real time.

By 2015, 95% of sample delivered via Lucid was coming from API integrated suppliers.

Buyers: Rethinking Traditional Sampling

It took a while, but today, sample buyers use three distinct methods of acquiring sample: Manual (traditional), interfaces (DIY), and API.

Manual (or traditional) sampling means companies still send bids over email and manually field a survey with a project manager assigned by the sample company. Generally, this method is shrinking in value because it’s slower, more expensive, and has more fielding error involved. However, it can be vital for hard-to-reach audiences and very complex fielding plans.

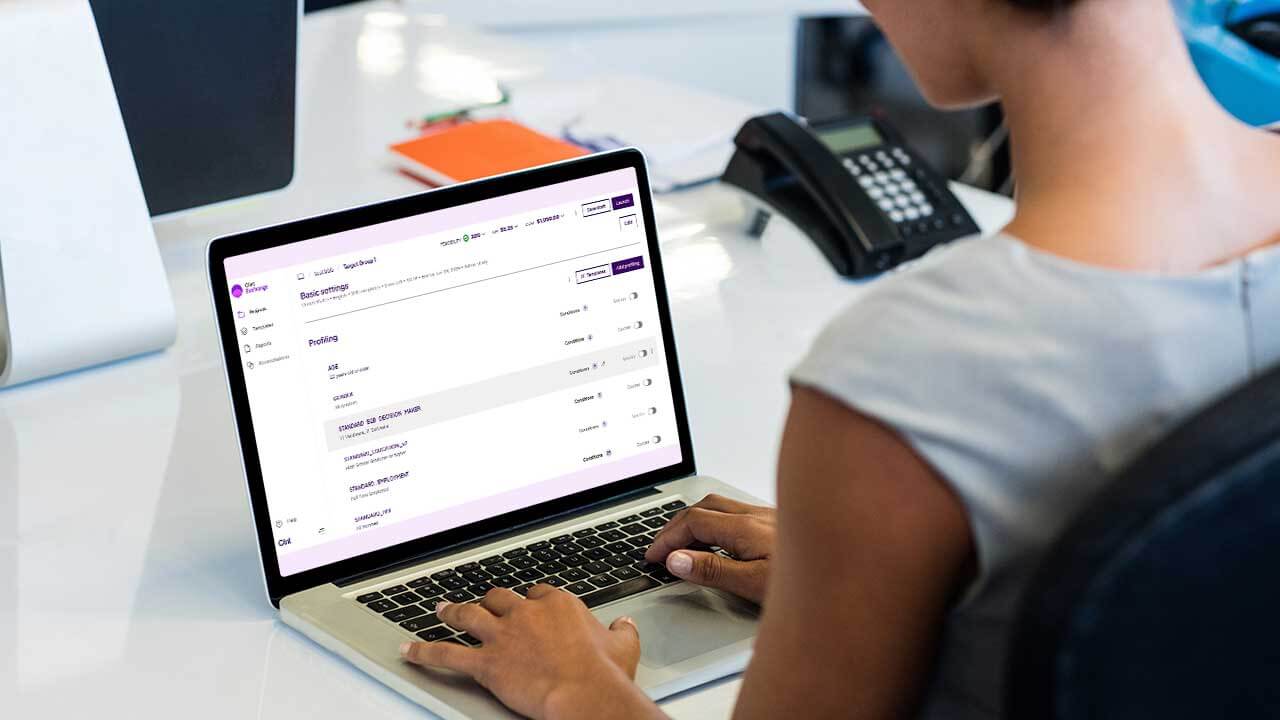

Sampling interfaces – such as DIY tools – give sample buyers more control, speed, and price efficiency than direct access to sample companies. But, this method requires training. With great power comes great responsibility. Additionally, much of the management of DIY fielding shifts to the buyer, whereas “manual” lies squarely on the sample supplier’s plate. So, these interfaces are important. Interfaces are what make it easy for researchers to price, manage, and deliver sample into research studies.

Finally we get to Buyer APIs – meaning if the buyer has a platform, like a survey tool, they can integrate directly via an API. You may find it hard to believe, but most researchers can’t actually engage directly with an API (and they are even less likely to read API documentation); so, they rely on interfaces that make it easy for them to price, manage, and deliver sample into research studies. However, with all the sample suppliers (and many buyers) releasing APIs, everyone has to integrate into something. That something is a platform like Lucid.

In recent years, we’ve seen APIs create a profound breakthrough in sampling technology. It’s given way to a new era of sampling that is programmatic, automated, and marketplace-driven. Essentially, an API embeds the sampling capability inside the tech stack or product of the sample buyer. Thus, it eliminates the need for a user to ever learn an interface or engage with a project manager.

What we find is that many sample buyers are using all three, depending on the situation. Manual sample delivery brings in the expertise of a sample project manager, along with the guarantee of delivery. Direct services allow buyers to rely on the expertise of a sample company for delivery or offload spikes of workload. Interfaces give speed, control, and pricing to the buyer – and those platforms tend to be the most robust in terms of fielding features.

Marketplaces: OMG! The Rocket Takes Off! (2016 – present)

If APIs creating programmatic connections was the “new dawn” of sample, then marketplaces are the supernova of change in the research industry.

Before marketplaces, decisions about buying, selling, pricing, and delivery were people-driven. Marketplaces, just like with a stock exchange, let the machines do the talking at a huge scale. The transition to marketplace dynamics has been one of the fastest technology changes in the industry and took many by surprise – including ourselves.

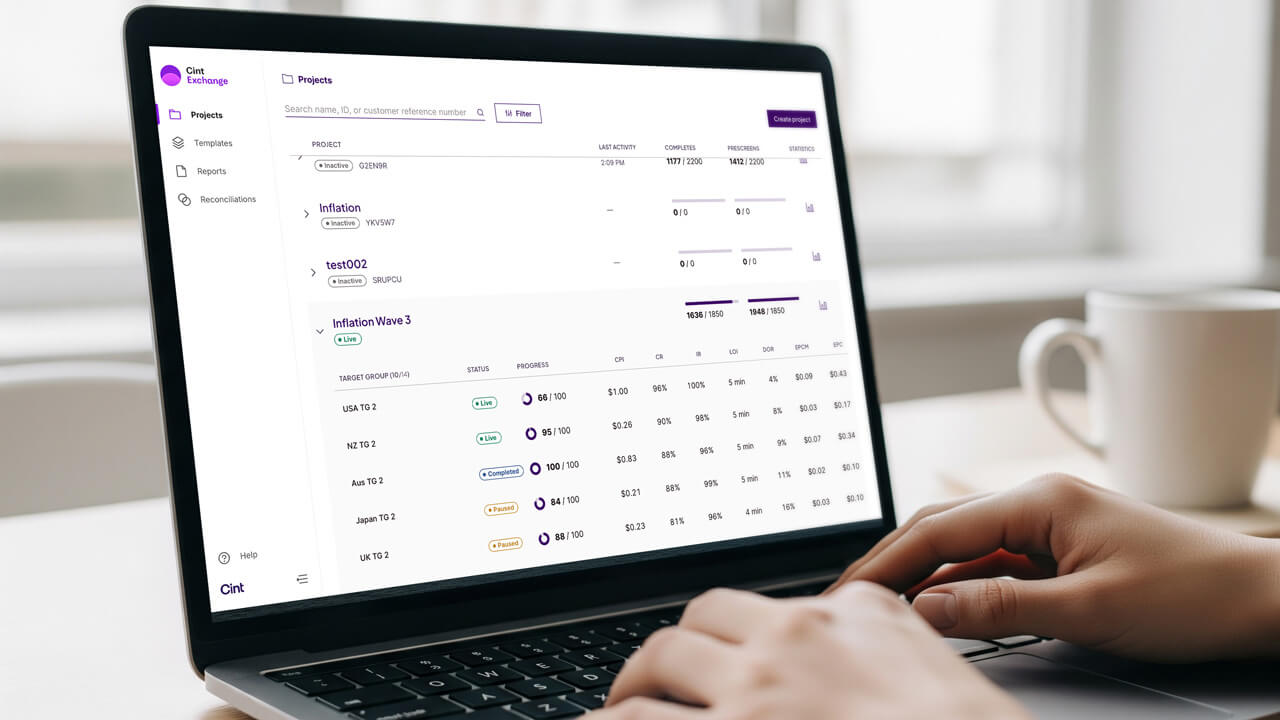

Essentially, a marketplace aggregates survey inventory from thousands of researchers and provides the real-time details of those surveys to hundreds of suppliers. We’ve named ours the Lucid Marketplace because that’s exactly what is is – a transparent, open marketplace.

An open marketplace enables real-time pricing and delivery of surveys in-field. This is important for a number of reasons:

- All suppliers have equal access to surveys.

- No supplier is mandated to deliver to any survey.

- The buyer and supplier are known to each other (transparency).

- A reverse fielding auction determines the most efficient CPI for the survey at any given time.

Another essential value of a marketplace is that it extracts the nuance and removes the differences between the API capabilities of hundreds of buyers and suppliers – into a single unified relationship.

But, integrating into a platform is a detailed process. Developing and maintaining a robust API integration is hard work. Not just the initial build, but the maintenance itself is ongoing. Because the buyer and seller technology is constantly improving and changing, the API integration (the connection between parties) has to be monitored and improved.

However, with a platform like Lucid, the required integrations are reduced to just one – because we handle all the monitoring and maintenance of so many integrations into our platform. Our platform also gives users control over their own processes, to whatever degree they want, allowing sample project managers to field all aspects of a survey from screening, qualifications, quotas, supplier management, reconciliations, and payments.

For suppliers, our marketplace dynamics are ideal. That’s because participation in a true, open marketplace means every sale is an opportunity to create brand recognition. It’s also a win for buyers because they know exactly where their sample is coming from. Unlike a private marketplace, the Lucid Marketplace doesn’t manipulate pricing or blend sample without a buyer’s knowledge. Plus, with the speed and scale offered by our technology, buyers gain quick access to hundreds of sample suppliers across the globe.

The Programmatic Sampling Marketplace: Everyone Wins

Programmatic delivery, along with marketplace dynamics, offers the precision, efficiency, and transparency that traditional routing could not. Ultimately, each supplier can view all available survey inventory and recruit the best respondent from their panel. Programmatic technology provides the information suppliers need to decide for themselves which respondent goes into which survey. Our API enables suppliers to earn revenue more efficiently, while simultaneously providing a better respondent experience that reflects their own business prerogatives.

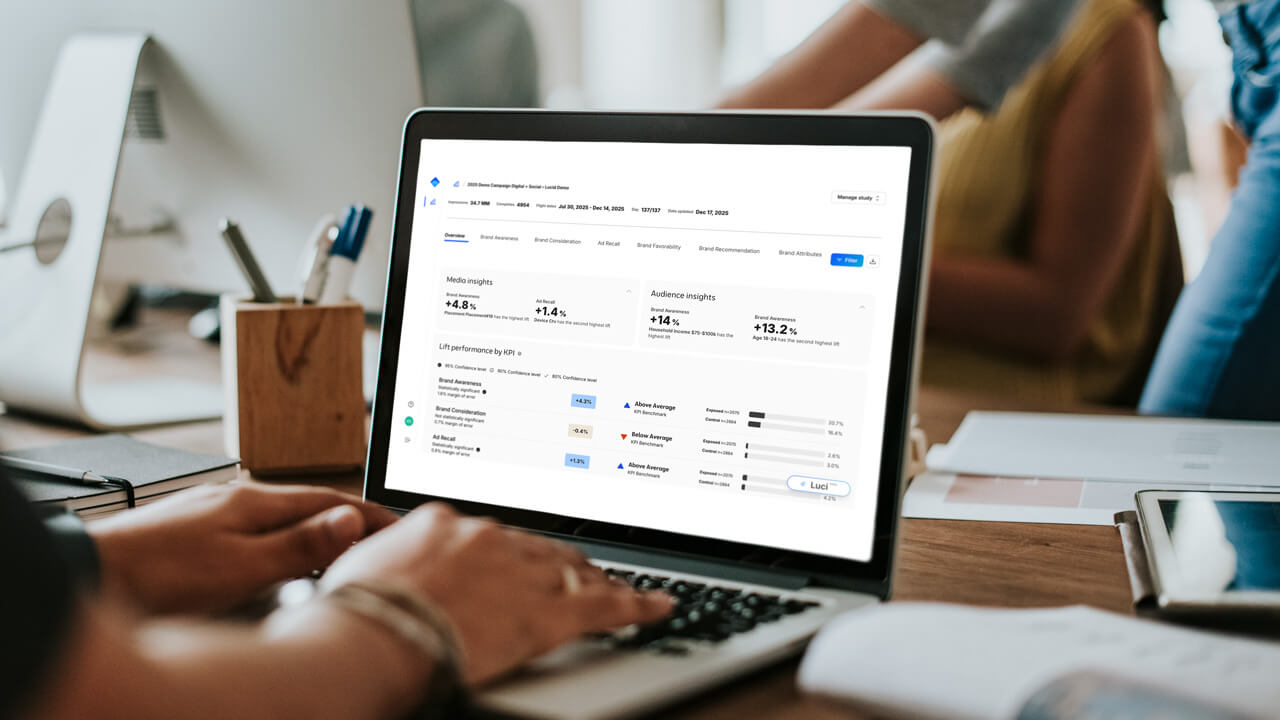

Similarly, for buyers, programmatic delivery makes it easier to get the required sample. Not only is the fielding process much easier on project managers, but the efficiency that suppliers get flows through to the researcher through less weary, more attentive respondents.

In the programmatic sampling era, suppliers gain significant cost efficiencies, buyers get sample faster – without the headache of manual bidding – and respondents spend less time trying to complete a survey. We’ve seen LOIs go down and both conversion and incidence rates go up. Everyone wins!

Cint continuously explores and develops the technology to move the industry forward. We love using new technologies to create solutions that make online research easier, smarter, and faster than ever before. We are confident that the best days are yet to come.